Viking

Viking Symbol – Viking Rune

Welcome! After reading this article, please check out our online Viking Sons of Odin Store with over 1000 unique items including necklace, bracelets, t shirt, hoodie, sweater, accessory, decoration and more.

A quick note about Norse Symbols

We sell hundreds of Norse jewelry items with various symbols, so it is helpful to understand their true origins and background. Most of these iconic images were used by the Norse before and during the Viking era, though the original true meanings of some are simply educated guesses by archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians.

A few symbols that are considered “Norse” have no proof of ever being used during the Viking era, such as the Troll Cross (not shown) which is based on later Swedish folklore and modern artistic interpretation, and two other very popular symbols known as the Helm of Awe (Icelandic: Ægishjálmur, Old Norse Œgishjalmr) and the Viking Compass (Icelandic: Vegvísir, for “signpost” or “wayfinder”). Those two symbols were found in Icelandic books from the 19th century. We offer an entire separate article discussing these two symbols and the controversy of their origin.

Why include Celtic symbols?

By the end of the Viking era, Vikings were already beginning to blend with the cultures they settled in. Many of the last few generations of these Vikings were often the children of a Celtic mother …or Slavic, English, etc. The National Museum of Ireland states the following on their website:

“By the end of the 10th century the Vikings in Ireland had adopted Christianity, and with the fusion of cultures it is often difficult to distinguish between Viking and Irish artifacts at this time.”

Article continued below.

|

Runes (Norse Alphabet) |

|

Valknut (Knot of the Slain) |

|

Ægishjálmr (Icelandic Helm of Awe) |

|

Vegvisir (Icelandic Compass) |

|

Triskele (Horns of Odin) |

|

Triquetra (Celtic Knot) |

|

Mjolnir (Thor’s Hammer) |

|

Viking Axe (Norse Weapon) |

|

Yggdrasil (Tree of Life) |

|

Longship (Viking Ships) |

|

Web of Wyrd (Fate) |

|

Gungnir (Odin’s Spear) |

|

Raven (Hugin and Munin) |

|

Wolf (Fenrir) |

|

8-Legged Horse (Sleipnir) |

|

Dragon (Norse Serpents) |

|

Boar (Nordic and Celtic) |

|

Cats, Bears (and more) |

Brief Overview of Norse Symbols

Symbols played an important role in Norse culture.

The spirituality of the Norse Vikings was so ingrained in their culture and thought process that they had no word for religion. There was no separation (as there so often is today) between faith and reality. The cosmic forces and fate were active in everything. Thanks to the Marvel movies, nearly everyone now knows about Thor’s hammer (Mjölnir) which was a very popular choice for Vikings to use in their jewelry as represented in this ancient Danish artifact to the right.

The Vikings also had letters (known as runes), but writing itself was sacred and even magical. So, while the Norse culture was very rich in poetry, stories, and songs, this was all transmitted orally. The stories of Odin, Thor, Freya, or the Viking heroes that we have now were all passed on by careful word of mouth until they were finally written down as the sagas by descendants of the Vikings centuries later. Symbols and motifs visually convey (instantly and across language barriers) messages that were deeply meaningful to the women and men that held them.

Symbols themselves were thought to have power.

Vikings sailed at the mercy of the mighty seas. They were intimately acquainted with the dangers of battle. Whether as warriors or as settlers, they lived in the wind, rain, heat, and cold. They depended on the bounty of the land to feed their children. Through everything, they felt the hand of fate governing all things. Divine symbols on amulets, boundary stones, stitched onto clothing, painted on shields, carved into their longships, or as items around their hearths could offer the Viking that small edge he or she needed to face the uncertainties and dangers of life.

Symbols and Motifs

The difference between symbols and motifs is simply a question of formality. A symbol is an established, recognized visual image that is almost always rendered in a specific way. Because of this, symbols tend to be very simple (so that almost anyone can draw them). Don’t let that fool you – symbols are usually considered to be older and more powerful than motifs or written words. Things like Mjölnir, the Valknut, or the Helm of Awe are symbols. Motifs are much less formal and can vary greatly from one artist to another. Motifs are meant to call something to mind, and though they can attract the attention of the gods (especially images of the god’s familiar, such as Odin’s ravens or Freya’s cats) they are not necessarily “visual spells” the way symbols are. Because of this flexibility, new interpretations of ancient Viking motifs are still being made today.

Following is a brief introduction to some common Norse symbols and motifs. The list is not all-inclusive, nor is it meant to be exhaustive but rather just a basic starting point. Remember, a picture is worth a thousand words.

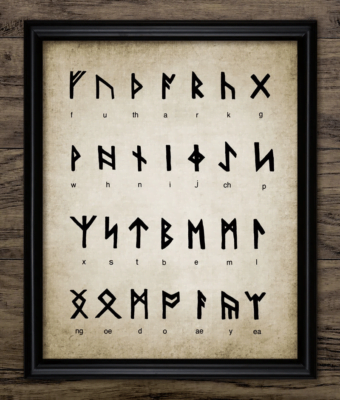

Runes (Norse Alphabet)

In the most basic sense, runes were letters, but the word rune also comes from the word for ‘secret’. Runes denoted phonetic sounds (like letters) but also had individual meanings (like the glyphs of other ancient languages). Runic alphabets are called futharks. Just as our term “alphabet” comes from the first two Greek letters (alpha and beta), the first six runes are F, U, Th, A, R and K. The oldest known futhark arose sometime between the second and fourth century, which is not surprising considering that was the time when war and trade between Germanic and Mediterranean peoples were accelerating.

In the most basic sense, runes were letters, but the word rune also comes from the word for ‘secret’. Runes denoted phonetic sounds (like letters) but also had individual meanings (like the glyphs of other ancient languages). Runic alphabets are called futharks. Just as our term “alphabet” comes from the first two Greek letters (alpha and beta), the first six runes are F, U, Th, A, R and K. The oldest known futhark arose sometime between the second and fourth century, which is not surprising considering that was the time when war and trade between Germanic and Mediterranean peoples were accelerating.

The Vikings had an oral culture and did not use runes to write just anything. Runes had power. They were seldom (if ever) penned onto parchment, as the enemies of the Vikings did in France, Ireland, and England; they were carved into wood, stone, metal, or bone (hence their angular appearance). Most of our surviving examples of runes are inscriptions on rune stones commemorating the lives of great rulers. Runes also had expressly magical purposes and were engraved on amulets, talismans, beads, and shields to ensure protection and victory.

Rune casting was another magical use of runes in the Viking Age. Rune casting or “casting rune sticks” involves spilling pieces of bone or wood (each carved with a rune) onto a piece of cloth. The skilled practitioner then deciphers the message rendered, not only of the runes but also their orientation to each other (similar to Tarot, in which the same card can have very different meanings depending on context).

Valknut (Knot of the Slain)

The Vikings believed that people who lived ordinary lives went on to a shadowy existence after death, but those who died gloriously in battle lived on in Valhalla. The Valkyries would carry the souls of these heroes from the battlefield. In Valhalla, they would live the Viking version of the good life: fighting great battles against each other every day but – in their immortal state – spending each night in revelry and feasting. This paradise comes with a price, though. For the slain warriors are Odin’s army, and they will join the gods in the last, great battle of Ragnarok. They will fight this doomed battle against the giants and fearsome creatures of darkness for the sake of our world and the world of the gods.

The Valknut is most-commonly believed to be the symbol of these slain warriors. The exact meaning of the three interlocking triangle shapes is unknown. Clues arise from Celtic and Neolithic art from Northwestern Europe in which interlinking triple shapes are common indicators of magical power and magical essence. Experts hypothesize that the Valknut may depict the cyclical path between life and death that these warriors experience. Others believe that the nine points represent the nine worlds of Norse mythology. Yet another theory holds that this symbol is the same as Hrungnir’s Heart, a triangular symbol described (but not pictured) by Snorri Sturluson in the Prose Edda. Hrungnir was a fearsome giant – the only giant that was ever able to wound Thor – so in some ways Hrungnir may also symbolize death.

While the details are lost to time, the Valknut symbol now calls to mind courage, bravery, and destiny throughout this life and the next.

Ægishjálmr (Helm of Awe)

The Ægishjálmr, or Helm of Awe, is a magical Icelandic symbol of protection and victory. The Helm of Awe is mentioned in several of the Eddic poems as being used by both warriors and even dragons! The symbol itself survives from later Icelandic grimoire (books of magic), penned well after the Viking Age but from an unbroken intellectual lineage to sea traveling Vikings of earlier times. The term “helm” means protective covering (i.e., helmet). But while some sources describe the Ægishjálmr as a magical object, most sources describe it more as an invisible spell that creates a sphere of protection on the user while casting fear and defeat on an enemy.

In the Saga of the Volsungs, Fafnir says of the Ægishjálmr, “I wore my terror-helmet against all men …and I blew poison in every direction before me so that no man dared to come near me, and I feared no weapon. I never faced so many men that I did not feel myself much stronger than they were, and everyone feared me.”

The eight arms or rays emit from the center point of the symbol. The arms themselves appear to be constructed from two intersecting runes. These are Algiz runes for victory and protection intersected by Isa runes, which may mean hardening (literally, ice). So, the hidden meaning of this symbol may be the ability to overcome through superior hardening of the mind and soul.

Vegvisir (Viking Compass)

The Vegvisir means “That Which Shows the Way.” It is an Icelandic magical stave, similar shape to the Helm of Awe, but while each of the arms of the helm is the same, the arms of the Vegvisir are all different. The Icelandic symbol was a visual spell of protection against getting lost (particularly at sea) – something that would have been very, very important to the Vikings. The Vikings may have had directional finding instruments of their own, such as the Uunartoq disc and sunstones; but most of their navigation came down to visual cues (the sun, stars, flight patterns of birds, the color of water, etc.)..

Given the potentially disastrous consequences inherent in such sea voyages, however, it is easy to see why Vikings would want magical help in keeping their way. The symbol comes down to us from the Icelandic Huld Manuscript (another grimoire) which was compiled in the 1840s from older manuscripts (now lost). The exact age of the Vegvisir is therefore unknown.

Modern technology has done a good job overcoming the dangers of becoming lost that were a grim reality for our ancestors, but the Vegvisir is not only protection against being unable to find one’s way in the physical world. For many people, the Vegvisir / Viking Compass represents staying on course in our spiritual voyage, and in finding our way through all the ups, downs, twists, and turns our lives can take. For a much deeper look at the history (and controversy) behind this symbol, click here.

Triskele (Horns of Odin)

The Horns of Odin (also referred to as the horn triskelion or the triple-horned triskele) is a symbol comprised three interlocking drinking horns. The exact meaning of the symbol is not known, but it may allude to Odin’s stealing of the Mead of Poetry. The horns’ names were Óðrœrir, Boðn, and Són. The symbol has become especially significant in the modern Asatru faith. The Horns of Odin symbol is also meaningful to other adherents to the Old Ways, or those who strongly identify with the god Odin.

The symbol appear on the 9th-century Snoldelev Stone (found in Denmark and seen to the right). While the shape of this symbol is reminiscent of the Triqueta and other Celtic symbols, it appears on the Larbro stone (in Gotland, Sweden) which may be as old as the early eighth century. On this image stone, the Horns of Odin are depicted as the crest on Odin’s shield. Because of its association with the Mead of Poetry and Odin’s artistic aspects, it might also be worn to bring inspiration to writers and performers.

Triquetra (Celtic Knot)

The Triquetra or the Trinity Knot is comprised one continuous line interweaving around itself, meaning no beginning or end, or eternal spiritual life. This symbol was originally Celtic, not Norse, but with increased contact and assimilation between the Vikings and the peoples of Ireland and Scotland, the Triquetra and other Celtic symbols/motifs became culturally syncretized.

A similar design was found on the Funbo Runestone found in Uppland, Sweden (seen to the right). Originally, the Triquetra was associated with the Celtic Mother Goddess and depicted her triune nature (the maiden, the mother, and the wise, old woman). The triple identity was an essential feature in many aspects of druidic belief and practice. Later, Irish and Scottish monks adopted the Triquetra as a symbol of the Christian Trinity. People today wear the Triquetra for any of these reasons and to be reminded of the continuity and multi-faceted nature of higher truths.

Mjölnir

Mjölnir (me-OL-neer) means grinder, crusher, hammer and is also associated with thunder and lightning. When the Vikings saw lightning, and heard thunder in a howling storm, they knew that Thor had used Mjölnir to send another giant to his doom. Thor was the son of Odin and Fyorgyn (a.k.a., Jord) the earth goddess. He was the god of thunder and the god of war and one of the most popular figures in all of Norse mythology. While Viking jarls and kings easily identified with wise, cunning Odin, Thor’s boundless strength, bravery, fortitude, and straightforwardness appealed more to the common Viking freeman. Mjölnir is known for its ability to destroy mountains. But it was not just a weapon.

The origin of Mjölnir is found in Skáldskaparmál from Snorri’s Edda. Loki made a bet with two dwarves, Brokkr and Sindri (or Eitri) that they could not make something better than the items created by the Sons of Ivaldi (the dwarves who created Odin’s spear Gungnir and Freyr’s foldable boat skioblaonir). The result was the magical hammer that was then presented to Thor as described in the following:

Then he gave the hammer to Thor, and said that Thor might smite as hard as he desired, whatsoever might be before him, and the hammer would not fail; and if he threw it at anything, it would never miss, and never fly so far as not to return to his hand; and if be desired, he might keep it in his sark, it was so small; but indeed it was a flaw in the hammer that the fore-haft (handle) was somewhat short. — The Prose Edda

Thor also used Mjölnir to hallow, or to bless. With Mjölnir, Thor could bring some things (such as the goats who drew his chariot) back to life. Thor was invoked at weddings, at births, and at special ceremonies for these abilities to bless, make holy, and protect.

Hundreds of Mjölnir amulets have been discovered in Viking graves and other Norse archaeological sites. Some experts have postulated that these amulets became increasingly popular as Vikings came into contact with Christians, as a way to differentiate themselves as followers of the Old Ways and not the strange faith of their enemies. This may or may not be true. Certainly, amulets of many kinds have been in use since pre-historic times. Interestingly, Mjölnir amulets were still worn by Norse Christians (sometimes in conjunction with a cross) after the Old Ways began to fade, so we can see that the symbol still had great meaning even after its relevance to religion had changed. With its association with Thor, the protector god of war and the of nature’s awe, the Mjölnir stands for power, strength, bravery, good luck, and protection from all harm. It is also an easily-recognizable sign that one holds the Old Ways in respect.

Viking Axe

The most famous, and perhaps most common, Viking weapon was the axe. Viking axes ranged in size from hand axes (similar to tomahawks) to long-hafted battle axes. Unlike the axes usually depicted in fantasy illustrations, Viking axes were single-bitted (to make them faster and more maneuverable). Viking axes were sometimes “bearded,” which is to say that the lower portion of the axe head was hook-shaped to facilitate catching and pulling shield rims or limbs. The axe required far less iron, time, or skill to produce than a sword; and because it was an important tool on farms and homesteads, the Norse would have had them in hand since childhood. The Viking axe would make the Norsemen famous, and even after the Viking Age waned, the descendants of the Vikings (such as the Varangians of Byzantium or the Galloglass of Ireland) would be sought after as bodyguards or elite mercenaries specifically for their axe skill.

As the Vikings traveled East into lands held by the Balts and Slavs, they encountered peoples who worshipped a god called Perun (a.k.a. Perkūnas or Perkonis). Perun was a sky god and a god of thunder, like Thor. Like Thor, Perun was the champion of mankind, a protector from evil and slayer of monsters. Like Thor, he was a cheerful, invincible, red-bearded warrior who traversed the heavens in a goat-drawn chariot. The biggest difference between Perun and Thor seems to be that while Thor fought with his mighty hammer, Mjolnir, Perun fought with an axe. Even as numerous Mjolnir amulets have been discovered in Viking Age sites in Scandinavia, many axe-shaped amulets have been discovered in the Baltic, Russia, and Ukraine. The Russian Primary Chronicle mentions the Viking-led Rus under Sviatoslav the Brave validating a peace treaty by swearing oaths to Perun. This may indicate that as Vikings found new homes in the lands that are now Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania, and Latvia they found common ground with the people there through the shared characteristics of gods like Thor and Perun.

As a symbol, the axe stands for bravery, strength, and audacity. It is a reminder of heritage and the accomplishments of ancestors who bent the world to their will using only what they had. It is a symbol of the berserker, and all that entails. It conveys the heart or mind’s ability to cut through that which holds one back and to forge boldly ahead.

Yggdrasil (Tree of Life or World Tree)

Yggdrasil is the vast “ash tree” that grows out of the Well of Destiny (Urðarbrunnr). All nine worlds or nine dimensions are entwined in its branches and its roots. Yggdrasil, therefore, serves as a conduit or pathway between these nine dimensions that the gods might travel. If this all seems a little difficult to imagine, you are not alone. Remember, myth is a means for people to understand cosmic truth. For our ancestors, myths like these were as close as they could come to science; and even as quantum physics is difficult for many of us to “picture”, it is still our way of describing the truth as we have found it to be. Yggdrasil was a way of thinking about reality and about how different realities could be connected (maybe similar in some ways to modern multiverse theory).

As Dan McCoy of Norse-mythology.org points out, “Yggdrasil and the Well of Urd weren’t thought of as existing in a single physical location, but rather dwell within the invisible heart of anything and everything.” Yggdrasil is a distinctive and unique Norse-Germanic concept; but at the same time, it is similar conceptually to other “trees of life” in ancient shamanism and other religions. As a symbol, Yggdrasil represents the cosmos, the relationship between time and destiny, harmony, the cycles of creation, and the essence of nature.

Longship

The longship was the soul of the Viking. The word “Viking” does not simply mean any medieval Scandinavian, but rather a man or woman who dared to venture forth into the unknown. The longship was the means by which that was accomplished. We have eyewitness accounts from centuries before the Vikings that tell us the Norse always were into their ships, but technological advances they made in ship design around the eighth century revolutionized what these ships were able to do. The Viking ships could row with oars or catch the wind with a broad, square sail. They were flexible and supple in the wild oceans. They were keeled for speed and precision. Most importantly to Viking mobility and military superiority, they had a very shallow draught.

All this meant that Vikings could cross the cold seas from Scandinavia to places that had never heard of them, then use river ways to move deep into these lands all while outpacing any enemies who might come against them. It took the greatest powers in Europe a long time to even figure out how to address this kind of threat. It was no wonder that the Viking ships were called dragon ships, for it was as if an otherworldly force was unleashed upon the peoples of Europe. Accounts from the very first recorded Viking raid (Lindisfarne) even speak of monks seeing visions of dragons in a prophecy of this doom.

There are two ships that stand out in Norse Mythology. Nalgfar is the ship of the goddess, Hel. It is made from the fingernails of the dead. At Ragnarok it will rise from the depths, and – oared by giants and with Loki at its helm – it will cross the Bifrost bridge to lead the assault on Asgard. The gods have a longship, too, called Skíðblaðnir. Skíðblaðnir is Frey’s ship, and while it is big enough to fit all the gods along with their chariots and war gear, the dwarves made it so cunningly that it can be folded up and carried around in a small bag or pocket. The gods use Skíðblaðnir to travel together over sea, over land, and even through the air. This myth shows how the Vikings viewed ships – a good ship can take you anywhere.

The relationship of the Vikings to their ships is even more striking when we realize that – in some ways – these ships were glorified boats, and not what we think of as ships at all. A Viking was completely exposed to the elements and could reach down and touch the waves. In such a vessel you would feel the waters of the deep slipping by just underneath of your feet as sea spray pelted your face. The Vikings sailed these vessels all the way to the Mediterranean, to Iceland and Greenland, and even all the way to North America. This level of commitment, acceptance of risk, rejection of limitations, and consuming hunger to bend the world to one’s will is difficult for many of us to accurately imagine. That is why the dragon ship will always symbolize the Vikings and everything about them.

Web of Wyrd

The Vikings believed all things – even the gods themselves – were bound to fate. The concept was so important that there were six different words for fate in the Old Scandinavian tongues. It was in large part this deep conviction that “fate is inexorable” that gave the Vikings their legendary courage. Because the outcome was determined, it was not for a man or a woman to try to escape their fate – no matter how grim it might be. The essential thing was in how one met the trials and tragedies that befell them.

In Norse mythology, fate itself is shaped by the Norns. The Norns are three women who sit at mouth of the Well of Urd (Urd and Wyrd both mean “fate” in different dialects) at the base of Yggdrasil, the world tree. There they weave together a great tapestry or web, with each thread being a human life. Some sources, including the Volsung saga, say that in addition to the three great Norns (who are called Past, Present, and Future) there are many lesser Norns of both Aesir and elf kind. These lesser Norn may act similarly to the idea of the guardian angels of Christianity or the daemon of Greco-Roman mythology.

The Web of Wyrd symbol represents the tapestry the Norns weave. It is uncertain whether this symbol was used during the Viking Age, but it uses imagery the Vikings would instantly understand. Nine lines intersect to form the symbol. Nine was a magic number to the Norse, and within the pattern of these lines all the runes can be found. The runes also sprang from the Well of Urd, and carried inherent meaning and power. Thus, when one looks at the nine lines of the Web of Wyrd, one is seeing all the runes at once, and seeing in symbolic form the secrets of life and destiny.

Gungnir

Gungnir is Odin’s spear, and a symbol that is closely associated with this god of inspiration, wisdom, and war. Gungnir was made for Odin by the sons of Invaldi, dwarves who were the master craftsman who also made the goddess Sif’s golden hair, and Frey’s famous ship, Skidbladnir. Gungnir is a magic spear, with dark runes inscribed on its point. Gungnir never misses its target.

When Odin sacrificed himself to discover the runes and the cosmic secrets they held, he stabbed Gungnir through his chest and hung from the world tree, Yggdrasil for nine days and nights. Because of this association, Vikings and earlier Germanic/Scandinavian peoples would also use a spear in conjunction with hanging for their sacrifices to Odin.

When Odin led the Aesir gods against the Vanir gods (before they made peace) he flung Gungnir over their heads, saying, “You are all mine!” The Vikings had a tradition of doing the same, and would commence their battles by throwing a spear over the ranks of their enemies as they shouted, “Odin take you all!” By symbolically sacrificing their enemies to Odin in this way, they hoped the Allfather would bring them victory.

As a symbol, Gungnir represents the courage, ecstasy, inspiration, skill, and wisdom of the Allfather, and it can be taken to represent focus, faithfulness, precision, and strength.

Raven

Ravens may be the animal most associated with the Vikings. This is because Ravens are the familiars of Odin, the Allfather. Odin was a god of war, and ravens feasting on the slain were a common sight on the battlefields of the Viking Age. The connection is deeper than that, however. Ravens are very intelligent birds. You cannot look at the eyes and head movement of a raven and not feel that it is trying to perceive everything about you – even weigh your spirit. Odin was accompanied by two ravens – Huginn (“Thought”) and Muninn (“Memory”). Huginn and Muninn fly throughout the nine worlds, and whatever their far-seeing eyes find they whisper back to Odin. Odin is often called hrafnaguð – the Raven God – and is often depicted with Huginn (HOO-gin) and Muninn (MOO-nin) sitting on his shoulders or flying around him.

Ravens are also associated with the 9th century Viking hero, Ragnar Lothbrok. Ragnar claimed descent from Odin through a human consort. This was something that did not sit well with the kings of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (as it implied parity with them), and for that and many other reasons they made war on him. Ragnar’s Vikings charged into battle with a raven banner flying above them, and each time they did, they were victorious

Various sagas and chronicles tell us Ragnar’s success led him to Finland, France, England, and maybe even as far as the Hellespont in Turkey, and wherever he went, he carried the raven banner with him. His sons Ivar and Ubbe carried the raven banner at the head of the Great Heathen Army that conquered the eastern kingdoms of England in the 9th century. The banner continued to bring victories until their descendant, Sigurd the Stout, finally died under it at the Irish Battle of Clontarf about 150 years later. Harald Hardrada (Hard-ruler), the larger-than-life Norse hero historians like to call “The Last Viking” also carried a raven banner he called “Land Waster.” When this raven banner finally fell in 1066, the Viking Age ended.

In Norse art, ravens symbolize Odin, insight, wisdom, intellect, bravery, battle glory, and continuity between life and the afterlife. For people today, they also represent the Vikings themselves, and the 200 years of exploits and exploration that these ancestors achieved. Raven coin shown here is a silver penny of Anlaf Guthfrithsson, Hiberno-Norse King of Northumbria (date: c. 939-941 AD).

Wolf

The wolf is a more enigmatic motif, as it can have several meanings. The most famous to the Vikings was Fenrir (or Fenris-wolf). Fenrir is one of the most frightening monsters in Norse mythology. He is the son of Loki and the giantess, Angrboða; the brother of the great sea serpent Jormungand, and of Hel, goddess of the underworld. When the gods saw how quickly Fenrir was growing and how ravenous he was, they tried to bind him – but Fenrir broke every chain. Finally, the dwarves made an unbreakable lashing with which the gods were able to subdue the creature – but only after he had ripped the god Tyr’s hand off. The gods placed a sword in Fenrir’s mouth to keep his jaws from snapping, and from his open, drooling mouth a river called Ván flowed as the wolf dreamed of his revenge. Fenrir is fated to escape someday, at the dawning of Ragnarok, and will devour the sun and moon and even kill Odin in the last days.

Not all the wolves in Norse culture were evil. Odin himself was accompanied by wolves, named Geri and Freki (both names meaning, Greedy) who accompanied him in battle, hunting, and wandering. This partnership between god and wolves gave rise to the alliance between humans and dogs.

The most famous type of Viking warriors is the berserker – men who “became the bear” and fought in states of ecstatic fury, empowered by the spirit of Odin. There was also a similar type of Viking warrior called an úlfheðnar, which means “wolf hides” (or werewolf). It is not entirely clear whether this was a synonym or a separate class of berserker. Some sources seem to hint that the úlfheðnar could have been like berserkers, but unlike the berserker (who fought alone ahead of the Viking shield walls) the úlfheðnar may have fought in small packs. We may never know for certain. What we do know is that the wolf was sacred to Odin and that some Vikings could channel the wolf to become impervious to “iron and fire” and to achieve great heights of martial prowess and valor in battle.

The wolf has both positive and negative connotations in Norse culture. The wolf can represent the destructive forces of time and nature, for which even the gods are not a match. The wolf can also represent the most valued characteristics of bravery, teamwork, and shamanistic power. The unifying characteristic in these two divergent manifestations is savagery and the primal nature. The wolf can bring out the worst or the best in people.

8-Legged Horse

Sleipnir (SLAPE-neer), also known as The Sliding One is Odin’s eight-legged stallion, and is considered by all the skalds to be “the best of horses.” This title should be no wonder, as Sleipnir can leap over the gates of Hel, cross the Bifrost bridge to Asgard, and travel up and down Yggdrasil and throughout the Nine Worlds. All this he can do at incredible speeds. While the other gods ride chariots, Odin rides Sleipnir into battle.

Sleipnir has a weird family. He was conceived when the god Loki shape-shifted into a mare to beguile the giant stallion, Svaðilfari (all so that Loki could get the gods out of an ill-advised contract with Svaðilfari’s owner – whom Thor killed anyway). Therefore, Sleipnir is the brother of the World-Coiling Serpent, Jörmungandr and the super-wolf, Fenrir.

Some experts hypothesize that Sleipnir’s octopedal sliding was inspired by the “tolt” – the fifth gait of Icelandic horses (and their Scandinavian ancestors) that make them very smooth to ride. While this may or may not be true, the idea of eight-legged spirit horses is a very, very old one. Sleipnir’s image, or rumors of him, appear in shamanistic traditions throughout Korea, Mongolia, Russia, and of course Northwestern Europe. As in Norse mythology, these eight-legged horses are a means for transporting souls across worlds (i.e., from life to the afterlife). These archeological finds are at least a thousand years older than Viking influence, showing that the roots of this symbol indeed go deep.

Sleipnir symbolizes speed, surety, perception, good luck in travel, eternal life, and transcendence. He combines the attributes of the horse (one of the most important and enduring animals to humankind) and the spirit. He is especially meaningful to athletes, equestrians, travelers, those who have lost loved ones, and those yearning for spiritual enlightenment.

Dragons (and Serpents)

The Vikings had lots of stories of dragons and giant serpents and left many depictions of these creatures in their art. The longship – the heart and soul of the Viking – were even called “dragon ships” for their sleek design and carved dragon-headed prows. These heads sometimes would be removed to announce the Vikings came in peace (as not to frighten the spirits of the land, the Icelandic law codes say). The common images of dragons we have from fantasy movies, with thick bodies and heavy legs come more from medieval heraldry inspired by Welsh (Celtic) legends. The earliest Norse dragons were more serpentine, with long coiling bodies. They only sometimes had wings, and only some breathed fire.

Some Norse dragons were not just giant monsters – they were cosmic forces unto themselves. Níðhöggr is such a creature. Níðhöggr means “Curse Striker.” He coils around the roots of Yggdrasil, gnawing at them and dreaming of Ragnarok. Jörmungandr (also called “The Midgard Serpent” or “The World-Coiling Serpent”) is so immeasurable that he wraps around the entire world, holding the oceans in. Jörmungandr is the arch-enemy of Thor, and they are fated to kill each other at Ragnarok.

Luckily, not all dragons were as big as the world – but they were big enough. Heroes like Beowulf met their greatest test against such creatures. Ragnar Lothbrok won his name, his favorite wife (Thora), and accelerated his destiny by slaying a giant, venomous serpent. One of the most interesting dragons was Fáfnir. Fáfnir was originally a dwarf, but through his greed and treachery, he was turned into a fearsome, almost-indestructible monster who slept on a horde of gold. Fáfnir (as well as Níðhöggr) exhibit one of the most frightening characteristics of dragons – dragons are not only big, powerful, and hard to kill; many of them are also highly intelligent. Dragons are as rich in symbolism as they were said to be rich in treasure. As the true, apex predator, dragons represent both great strength and great danger. With their association with hordes of gold or as the captors of beautiful women, dragons can represent opportunity through risk.

Though the Norse did not equate dragons with the Devil, as Christians do (remember, the Norse did not have a Devil), dragons like Fáfnir can sometimes represent spiritual corruption or the darker side of human nature. Most of all, dragons embody the destructive phase of the creation-destruction cycle. This means that they represent chaos and cataclysm, but also change and renewal.

Boars (Nordic and Celtic)

There are numerous other animal motifs in Norse art and culture. Many of these are the fylgja (familiars or attendant spirits) of different gods. Thor had his goats, and Heimdall had his rams. Freya had a ferocious boar to accompany her in war, named Hildisvini (“Battle Swine”). Her brother, Freyr (or Frey) – the god of sex, male fertility, bounty, wealth, and peace (who, along with Freya, aptly lends his name to Friday) – had a boar named Gullinborsti (“Golden-Bristled”) as his fylgia. Seeing Gullinborsti’s symbol or other boar motifs would make a Viking think of peace, happiness, and plenty. Boars are also significant in Celtic mythology, such as the fertility god Moccus, or the Torc Triatha of the goddess Brigid.

Cats, Bears (and other animals)

The Vikings believed cats were the spirit animals (flygjur or familiars) of the Vanir goddess, Freya. Freya (also spelled, Freyja, the name meaning “The Lady”) was one of the most revered, widely venerated, and most fascinating of all the Norse gods or goddesses. Freya was the goddess of love, sex, and romantic desire – but she was not just some northern version of Venus. Freya was a fearsome goddess of war, as well, and she would ride into battle on her wild boar, Hildisvini (“Battle Swine”). Like Odin, Freya also selected the bravest of slain warriors for the afterlife of Valhalla. Freya had other parallels to Odin, including her association with magic and arcane knowledge. Freya is said to have taught Odin much of what he knows of the secret arts. She is also a lover of poetry, music, and thoughtfulness.

As a Vanir goddess and the sister (some say, twin) of the god Frey (or Freyr), Freya is a goddess of prosperity and riches. Freya’s tears turn to gold or precious amber, and the names of her two daughters are Hnoss (“Precious”) and Gersimi (“Treasure”).

Freya is a fertility goddess. Though she cries her amber tears when she misses her wandering husband, skaldic poetry tells us that she has an unbridled sexuality. In Norse mythology, Freya is often depicted as the object of desire not only of gods but of giants, elves, and men, too.

When not riding Hildisvini into the thick of battle or using her fabulous falcon-feather cloak to shape shift into a lightning-fast bird of prey, Freya travelled in a chariot drawn by black or gray cats. Some folklorists see the image of the goddess getting cats to work together and go in the same direction as a metaphor for the power of feminine influence – a reoccurring theme in the Viking sagas. The cat probably reminded Vikings of Freya because of the common personality traits: cats are independent but affectionate when they want to be; fierce fighters and lethal hunters but lovers of leisure, luxury, and treasures. This association between the goddess of magic and her cats may be why cats became associated with witches during the later Middle Ages and through our own time.

In Norse art or jewelry, the symbol or motif of the cat is meant to denote the blessing or character of Freya, with all her contradictions and strength: love and desire, abundance and beauty, valor and the afterlife, music and poetry, magic and wisdom..

Bears

The bear was one of the most powerful and ferocious animals the Vikings knew. The very sight of a bear in the wild would make the bravest of men back away slowly. They are massive, fast, and deadly, and their hide and fur resist most weapons. It is easy to see why the Vikings would be fascinated by them and would want to emulate them.

Viking sea kings loved to own bears as pets. Saxo Grammaticus tells us that the great shield maiden, Lagertha, had a pet bear that she turned loose on Ragnar Lothbrok when he first came to court her. Understandably, this incident got brought up again in their later divorce. The Greenland Vikings specialized in exporting polar bears and polar bear furs to the courts of Medieval Europe.

The Bear was sacred to Odin, and this association inspired the most legendary class of all Vikings: the berserkers. Berserkers were Viking heroes who would fight in a state of ecstatic frenzy. The word berserker comes from two old Norse words that mean “bear shirt” or “bear skin.” It is also where we get the phrase,”to go berserk”. The berserker took on the essence and spirit of the great bears of the Scandinavian wilderness. He became the bear in battle, with all the creature’s ferocity, bravery, strength, and indestructibility. Thus, he put on the bear’s skin – which he may have also done literally, using bear hide for armor. Or, he wore no armor of any kind and had bare skin (the play on words is the same in English and Old Norse). In either case, the berserker was a warrior who entered battle furious and inspired with Odin’s lethal ecstasy.

Instead of fighting as a team, as other Vikings would, the berserker would sometimes go in advance of the line. The method to this madness was two-fold. His valor was meant to both inspire his comrades and to dishearten his foes. By single-handedly attacking the enemy lines (often with sweeping blows of the huge, powerful Dane axe) before his forces could make contact, he sought to disrupt the enemy’s cohesion and exploit holes in their defenses that his brothers in arms could drive through.

The skalds tell us that berserkers were impervious to iron or fire.

Other Animals

Sometimes animals were not just the ‘familiars’ of the gods but were the gods themselves. Odin’s wife Frigg could change into a falcon. Other animals were not the fylgja of the gods, but merely had the gods’ favor because of their characteristics and personality (in the same way that many of us see ourselves in certain animals). In addition to familiars, various animal spirits populate Norse mythology, such as the eagle who sits in the boughs of Yggdrasil, or the squirrel that scurries along the trunk of the world tree.